Code Cells¶

Code, Output, Streams¶

An empty code cell:

[ ]:

Two empty lines:

[ ]:

Leading/trailing empty lines:

[1]:

# 2 empty lines before, 1 after

A simple output:

[2]:

6 * 7

[2]:

42

The standard output stream:

[3]:

print('Hello, world!')

Hello, world!

Normal output + standard output

[4]:

print('Hello, world!')

6 * 7

Hello, world!

[4]:

42

The standard error stream is highlighted and displayed just below the code cell. The standard output stream comes afterwards (with no special highlighting). Finally, the “normal” output is displayed.

[5]:

import sys

print("I'll appear on the standard error stream", file=sys.stderr)

print("I'll appear on the standard output stream")

"I'm the 'normal' output"

I'll appear on the standard output stream

I'll appear on the standard error stream

[5]:

"I'm the 'normal' output"

Note

Using the IPython kernel, the order is actually mixed up, see https://github.com/ipython/ipykernel/issues/280.

Cell Magics¶

IPython can handle code in other languages by means of cell magics:

[6]:

%%bash

for i in 1 2 3

do

echo $i

done

1

2

3

Special Display Formats¶

Local Image Files¶

[7]:

from IPython.display import Image

i = Image(filename='images/notebook_icon.png')

i

[7]:

[8]:

display(i)

See also SVG support for LaTeX.

[9]:

from IPython.display import SVG

SVG(filename='images/python_logo.svg')

[9]:

Image URLs¶

[10]:

Image(url='https://www.python.org/static/img/python-logo-large.png')

[10]:

[11]:

Image(url='https://www.python.org/static/img/python-logo-large.png', embed=True)

[11]:

[12]:

Image(url='https://jupyter.org/assets/nav_logo.svg')

[12]:

Math¶

[13]:

from IPython.display import Math

eq = Math(r'\int\limits_{-\infty}^\infty f(x) \delta(x - x_0) dx = f(x_0)')

eq

[13]:

[14]:

display(eq)

[15]:

from IPython.display import Latex

Latex(r'This is a \LaTeX{} equation: $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$')

[15]:

[16]:

%%latex

\begin{equation}

\int\limits_{-\infty}^\infty f(x) \delta(x - x_0) dx = f(x_0)

\end{equation}

Plots¶

The output formats for Matplotlib plots can be customized. You’ll need separate settings for the Jupyter Notebook application and for nbsphinx.

If you want to use SVG images for Matplotlib plots, add this line to your IPython configuration file:

c.InlineBackend.figure_formats = {'svg'}

If you want SVG images, but also want nice plots when exporting to LaTeX/PDF, you can select:

c.InlineBackend.figure_formats = {'svg', 'pdf'}

If you want to use the default PNG plots or HiDPI plots using 'png2x' (a.k.a. 'retina'), make sure to set this:

c.InlineBackend.rc = {'figure.dpi': 96}

This is needed because the default 'figure.dpi' value of 72 is only valid for the Qt Console.

If you are planning to store your SVG plots as part of your notebooks, you should also have a look at the 'svg.hashsalt' setting.

For more details on these and other settings, have a look at Default Values for Matplotlib’s “inline” Backend.

The configuration file ipython_kernel_config.py can be either in the directory where your notebook is located (see the ipython_kernel_config.py in this directory), or in your profile directory (typically ~/.ipython/profile_default/ipython_kernel_config.py). To find out your IPython profile directory, use this command:

python3 -m IPython profile locate

A local ipython_kernel_config.py in the notebook directory also works on https://mybinder.org/. Alternatively, you can create a file with those settings in a file named .ipython/profile_default/ipython_kernel_config.py in your repository.

To get SVG and PDF plots for nbsphinx, use something like this in your conf.py file:

nbsphinx_execute_arguments = [

"--InlineBackend.figure_formats={'svg', 'pdf'}",

"--InlineBackend.rc={'figure.dpi': 96}",

]

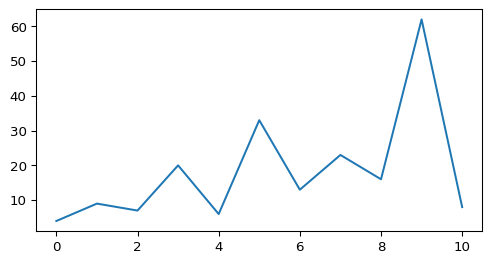

In the following example, nbsphinx should use an SVG image in the HTML output and a PDF image for LaTeX/PDF output.

[17]:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

/home/docs/checkouts/readthedocs.org/user_builds/nbsphinx/envs/0.7.1/lib/python3.7/site-packages/traitlets/traitlets.py:3036: FutureWarning: --rc={'figure.dpi': 96} for dict-traits is deprecated in traitlets 5.0. You can pass --rc <key=value> ... multiple times to add items to a dict.

FutureWarning,

[18]:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=[6, 3])

ax.plot([4, 9, 7, 20, 6, 33, 13, 23, 16, 62, 8]);

[18]:

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x7f44cfa0d828>]

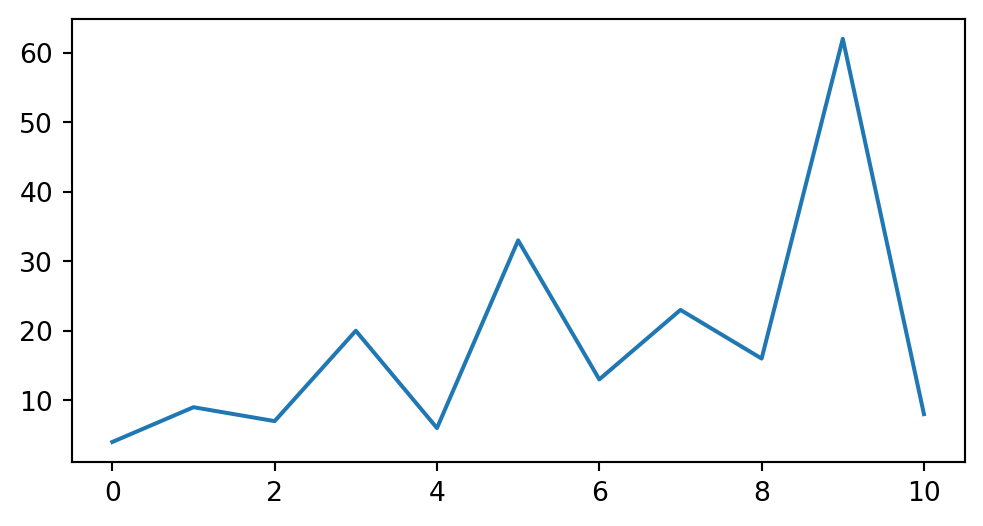

Alternatively, the figure format(s) can also be chosen directly in the notebook (which overrides the setting in nbsphinx_execute_arguments and in the IPython configuration):

[19]:

%config InlineBackend.figure_formats = ['png']

[20]:

fig

[20]:

If you want to use PNG images, but with HiDPI resolution, use the special 'png2x' (a.k.a. 'retina') format (which also looks nice in the LaTeX output):

[21]:

%config InlineBackend.figure_formats = ['png2x']

[22]:

fig

[22]:

Pandas Dataframes¶

Pandas dataframes should be displayed as nicely formatted HTML tables (if you are using HTML output).

[23]:

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

[24]:

df = pd.DataFrame(np.random.randint(0, 100, size=[5, 4]),

columns=['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'])

df

[24]:

| a | b | c | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 80 | 12 | 86 | 23 |

| 1 | 77 | 35 | 44 | 82 |

| 2 | 69 | 30 | 2 | 80 |

| 3 | 55 | 1 | 54 | 69 |

| 4 | 45 | 78 | 22 | 70 |

For LaTeX output, however, the plain text output is used by default.

To get nice LaTeX tables, a few settings have to be changed:

[25]:

pd.set_option('display.latex.repr', True)

This is not enabled by default because of Pandas issue #12182.

The generated LaTeX tables utilize the booktabs package, so you have to make sure that package is loaded in the preamble with:

\usepackage{booktabs}

In order to allow page breaks within tables, you should use:

[26]:

pd.set_option('display.latex.longtable', True)

The longtable package is already used by Sphinx, so you don’t have to manually load it in the preamble.

Finally, if you want to use LaTeX math expressions in your dataframe, you’ll have to disable escaping:

[27]:

pd.set_option('display.latex.escape', False)

The above settings should have no influence on the HTML output, but the LaTeX output should now look nicer:

[28]:

df = pd.DataFrame(np.random.randint(0, 100, size=[10, 4]),

columns=[r'$\alpha$', r'$\beta$', r'$\gamma$', r'$\delta$'])

df

[28]:

| $\alpha$ | $\beta$ | $\gamma$ | $\delta$ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 17 | 96 | 69 | 14 |

| 1 | 90 | 56 | 91 | 0 |

| 2 | 56 | 36 | 83 | 52 |

| 3 | 16 | 25 | 75 | 69 |

| 4 | 54 | 94 | 27 | 19 |

| 5 | 73 | 37 | 12 | 46 |

| 6 | 40 | 32 | 33 | 98 |

| 7 | 67 | 69 | 28 | 8 |

| 8 | 81 | 85 | 15 | 19 |

| 9 | 98 | 92 | 39 | 62 |

Interactive Widgets (HTML only)¶

The basic widget infrastructure is provided by the ipywidgets module. More advanced widgets are available in separate packages, see for example https://jupyter.org/widgets.

The JavaScript code which is needed to display Jupyter widgets is loaded automatically (using RequireJS). If you want to use non-default URLs or local files, you can use the nbsphinx_widgets_path and nbsphinx_requirejs_path settings.

[30]:

import ipywidgets as w

[31]:

slider = w.IntSlider()

slider.value = 42

slider

A widget typically consists of a so-called “model” and a “view” into that model.

If you display a widget multiple times, all instances act as a “view” into the same “model”. That means that their state is synchronized. You can move either one of these sliders to try this out:

[32]:

slider

You can also link different widgets.

Widgets can be linked via the kernel (which of course only works while a kernel is running) or directly in the client (which even works in the rendered HTML pages).

Widgets can be linked uni- or bi-directionally.

Examples for all 4 combinations are shown here:

[33]:

link = w.IntSlider(description='link')

w.link((slider, 'value'), (link, 'value'))

jslink = w.IntSlider(description='jslink')

w.jslink((slider, 'value'), (jslink, 'value'))

dlink = w.IntSlider(description='dlink')

w.dlink((slider, 'value'), (dlink, 'value'))

jsdlink = w.IntSlider(description='jsdlink')

w.jsdlink((slider, 'value'), (jsdlink, 'value'))

w.VBox([link, jslink, dlink, jsdlink])

Other Languages

The examples shown here are using Python, but the widget technology can also be used with different Jupyter kernels (i.e. with different programming languages).

Arbitrary JavaScript Output (HTML only)¶

[34]:

%%javascript

var text = document.createTextNode("Hello, I was generated with JavaScript!");

// Content appended to "element" will be visible in the output area:

element.appendChild(text);

Unsupported Output Types¶

If a code cell produces data with an unsupported MIME type, the Jupyter Notebook doesn’t generate any output. nbsphinx, however, shows a warning message.

[35]:

display({

'text/x-python': 'print("Hello, world!")',

'text/x-haskell': 'main = putStrLn "Hello, world!"',

}, raw=True)

Data type cannot be displayed: text/x-python, text/x-haskell

ANSI Colors¶

The standard output and standard error streams may contain ANSI escape sequences to change the text and background colors.

[36]:

print('BEWARE: \x1b[1;33;41mugly colors\x1b[m!', file=sys.stderr)

print('AB\x1b[43mCD\x1b[35mEF\x1b[1mGH\x1b[4mIJ\x1b[7m'

'KL\x1b[49mMN\x1b[39mOP\x1b[22mQR\x1b[24mST\x1b[27mUV')

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUV

BEWARE: ugly colors!

The following code showing the 8 basic ANSI colors is based on http://tldp.org/HOWTO/Bash-Prompt-HOWTO/x329.html. Each of the 8 colors has an “intense” variation, which is used for bold text.

[37]:

text = ' XYZ '

formatstring = '\x1b[{}m' + text + '\x1b[m'

print(' ' * 6 + ' ' * len(text) +

''.join('{:^{}}'.format(bg, len(text)) for bg in range(40, 48)))

for fg in range(30, 38):

for bold in False, True:

fg_code = ('1;' if bold else '') + str(fg)

print(' {:>4} '.format(fg_code) + formatstring.format(fg_code) +

''.join(formatstring.format(fg_code + ';' + str(bg))

for bg in range(40, 48)))

40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47

30 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

1;30 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

31 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

1;31 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

32 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

1;32 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

33 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

1;33 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

34 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

1;34 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

35 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

1;35 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

36 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

1;36 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

37 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

1;37 XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ XYZ

ANSI also supports a set of 256 indexed colors. The following code showing all of them is based on http://bitmote.com/index.php?post/2012/11/19/Using-ANSI-Color-Codes-to-Colorize-Your-Bash-Prompt-on-Linux.

[38]:

formatstring = '\x1b[38;5;{0};48;5;{0}mX\x1b[1mX\x1b[m'

print(' + ' + ''.join('{:2}'.format(i) for i in range(36)))

print(' 0 ' + ''.join(formatstring.format(i) for i in range(16)))

for i in range(7):

i = i * 36 + 16

print('{:3} '.format(i) + ''.join(formatstring.format(i + j)

for j in range(36) if i + j < 256))

+ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011121314151617181920212223242526272829303132333435

0 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

16 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

52 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

88 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

124 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

160 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

196 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

232 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

You can even use 24-bit RGB colors:

[39]:

start = 255, 0, 0

end = 0, 0, 255

length = 79

out = []

for i in range(length):

rgb = [start[c] + int(i * (end[c] - start[c]) / length) for c in range(3)]

out.append('\x1b['

'38;2;{rgb[2]};{rgb[1]};{rgb[0]};'

'48;2;{rgb[0]};{rgb[1]};{rgb[2]}mX\x1b[m'.format(rgb=rgb))

print(''.join(out))

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX